A number of shocking stories describing the barbaric abuse of Aboriginal people in Canada in the not-too-distant past have surfaced in recent weeks, again exposing the bluntly white-supremacist values that prevailed when today’s Elders were young. Old wounds among survivors and descendants of survivors are being painfully reopened.

Photograph of a group of boys and staff St. Anne’s Indian Residential School (Fort Albany, Ont.) originally created 1945 —- Credit- Algoma University Archives

In the last week, newly unearthed information exposed the deliberate and systematic starvation of Indigenous test subjects during the 1940s and 50s in the name of medical research. With federal government approval, researchers conducted secret nutritional and medical experiments on Aboriginal people without their consent or knowledge.

In another development, lawsuits were filed over the so-called “60s scoop” of Aboriginal children into white homes, as well as the alleged torture of children at St. Anne’s Residential School in Fort Albany, Ontario.

This wave of grim news is a lot to take in.

Food historian Ian Mosby exposed the starvation experiments. His research showed that, between 1942 and 1952, the Canadian scientists conducted a government-approved experiment involving intentional starvation on 1,300 Indigenous people, mostly helpless children interned in residential schools. The researchers, after observing the health impacts of starvation on desperately impoverished remote reserves, decided to use Aboriginal children to test the effectiveness of vitamin supplements.

Their goals may have been well intentioned. The post-war researchers rejected the prevailing prejudice against Natives as “shiftless, indolent, improvident and inert” because these were “inherent or hereditary traits in the Indian race.” Instead, they argued this was the result of malnourishment.

But rather than increasing support to the communities to enable them to feed themselves, the researchers instead decided to use the starving people as test-subjects for different diets (none of which even resulted in any useful findings). Some people were selected to receive vitamins, while others were chosen to continue starving as a control group. Thus schools were instructed to withhold milk, vitamins, iron and iodine from hungry children, while dental services for children were withdrawn because the researchers worried that dental hygiene would affect the study’s results.

Days after this news appeared, APTN reported on research by Brock University Professor Maureen Lux, who is finishing a book on the treatment of Aboriginal people in tuberculosis (TB) sanatoriums at the hands of the Canadian government. Lux’s research revealed that children on the Qu’Appelle reserve in southern Saskatchewan were used as test subjects for an untested TB vaccine between 1933 and 1945. This occurred at a time when medical officials had already determined that the best course of action to lower TB rates was to improve the desperate living conditions on reserves.

However, those improvements to impoverished conditions – which included digging wells, building frame houses, providing families with farm animals and feed, improving food supplied to children and pregnant women, and assigning nurses to care for children with infectious diseases in their homes – were more expensive. The federal government apparently hoped to save money by turning to vaccines.

In a campaign backed by Indian Affairs and the National Research Council, children at the Qu’Appelle reserve were given the controversial bacille Calmette-Guerin (BCG) vaccine, which doctors had not yet determined was fully safe. While the trial was officially deemed a success, over 100 of the 609 vaccinated children died anyway from non-TB diseases attributable to poverty-related malnutrition.

Finally, a class-action lawsuit on behalf of the 16,000 Indigenous children taken from their homes in the infamous 60s scoop is finally making it to court. To its shame, the federal government is asking a judge to tell it what to do with documents addressing conduct at the St. Anne’s Residential School between 1904 to 1976. These documents were collected during a 1990s police inquiry into allegations of abuse and torture at the school (including the use of a homemade electric chair to punish students as young as six).

The federal government argues that the documents cannot be released because they belong to the province of Ontario and because they may contain private statements made to police during the investigation. Aboriginal Affairs Minister Bernard Valcourt indicated July 22 that it would be best for the issue to be decided by the Ontario Superior Court.

Honour the apology

In response to the news of the experiments on Aboriginal children, Valcourt released a statement in which he said, “When Prime Minister Harper made a historic apology to former students of Indian Residential Schools in 2008 on behalf of all Canadians, he recognized that this period had caused great harm and had no place in Canada.”

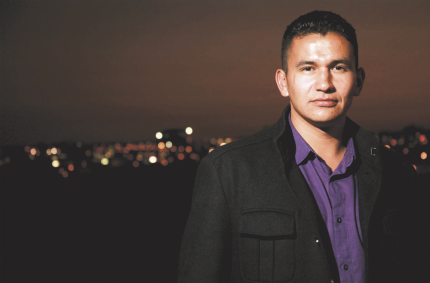

However, many people question the purpose of this blanket apology. One prominent voice asking that question is Wabanakwat (“Wab”) Kinew, an Onigaming Ojibwe journalist, activist, musician and Director of Indigenous Inclusion at the University of Winnipeg. Following the news of the nutritional experiments, Kinew and other Indigenous activists sprang into action, organizing “Honour The Apology” events across Canada on June 25 to demand that the federal government release all documents pertaining to Indian residential schools.

Reached in Winnipeg after a day that saw rallies in Vancouver, Edmonton, Saskatoon, Winnipeg, Thunder Bay, Sudbury, Toronto, Ottawa, Moose Creek, Opaskwayak and Whitehorse, Kinew was clearly pleased with the extraordinary cross-country mobilization.

“To me it says that most Canadians are on the same page as I am, which is that they think the apology was the right thing to do, they want the intents of the apology to be honoured, and they care about doing the right thing with regard to Indigenous people,” he observed.

Kinew said he has seen people taking different approaches to learning the painful truths around residential schools, as well as to the nutritional experiments and TB testing.

“It varies,” said Kinew. “Some communities are very concerned with reclaiming language and traditions as a way to respond to the residential school era. Other communities are fully Christianized – I don’t know how they reconcile it. They look at it as an era of transition, I guess.”

Above all, Kinew said, the common thread is an appreciation of the importance of supporting Elders who survived residential schools. It is vital that their experience be commemorated, above all by revitalizing the languages and cultures the schools were designed to destroy.

It’s critical to “make sure that we honour those people who have suffered in the past and do our best to make sure that they can live out the rest of their lives in comfort and in peace,” he said. “We should also make sure that those types of transgressions should not happen again in the future. Learning the truth about our history is one of the key ways in preventing history from repeating itself.”

As news about the nutritional experiments was breaking – and Kinew and others were pulling together to organize the Honour The Apology events – the pace of discussion was sped up thanks to social media. Kinew acknowledged that the Internet has greatly changed the way that Indigenous communities talk among themselves and to each other.

“Indigenous people are more connected than ever before, especially because of social media and in particular Facebook,” he said. “We’re able to communicate with each other, share information, and also to mobilize. That is new. I don’t think that existed the same way in the past. So for instance with this thing that we organized today, Honour the Apology, in some ways it used the same social networks as Idle No More did – some of the same contacts. The experience of having gone through Idle No More last winter made it easier to connect with people.”

As he underlined in his Honour The Apology essay, the need to put pressure on the government is becoming more crucial as the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s (TRC) nears the end of its mandate. Kinew worries that the TRC will not get all the documents it requires, and will therefore leave the task of coming to terms with residential schools unfinished.

“I think what’s likely to happen is that [the TRC] will get some documents, but far fewer than they should,” he said. “The minister today said that he’s handed over 900 documents out of the ones that the TRC was asking for. But the TRC says that there are over a million – 900 out of a million is a drop in the bucket, less than 0.1%. If it’s taken them this long to turn over 900, how many are they going to turn over by next year?

“First Nations people and other people affected by residential schools in the Indigenous community, we will miss out on a very important step on the healing journey. That is to have full disclosure and a full acknowledgement of everything that happened to the survivors, and to our grandparents and parents and aunties and uncles who were affected by this.”

Though information about such events as the nutritional and TB experiments is disturbing, said Kinew, “in the end we need to know. We want to know. In that way, we can look that ugliness in the face, and then turn the page and move on together.”

If such traumatic information isn’t revealed by the TRC, he went on, it will nonetheless be discovered piece by piece in the future by other researchers.

“And then we’ll have these wounds being pulled open again,” he said. “Which is very damaging, obviously, to the survivors, but also to people such as myself who are the descendants of survivors.”

Canada’s treatment of Aboriginal peoples is a black mark on its reputation, concluded Kinew. “Canada is a great nation with a troubled history. We can send a clear message that Canada has turned the page and is a country that is proud of and celebrates its indigenous people. But the way to do that is to fully participate in disclosing the truth, and therefore paving the way toward reconciliation.”