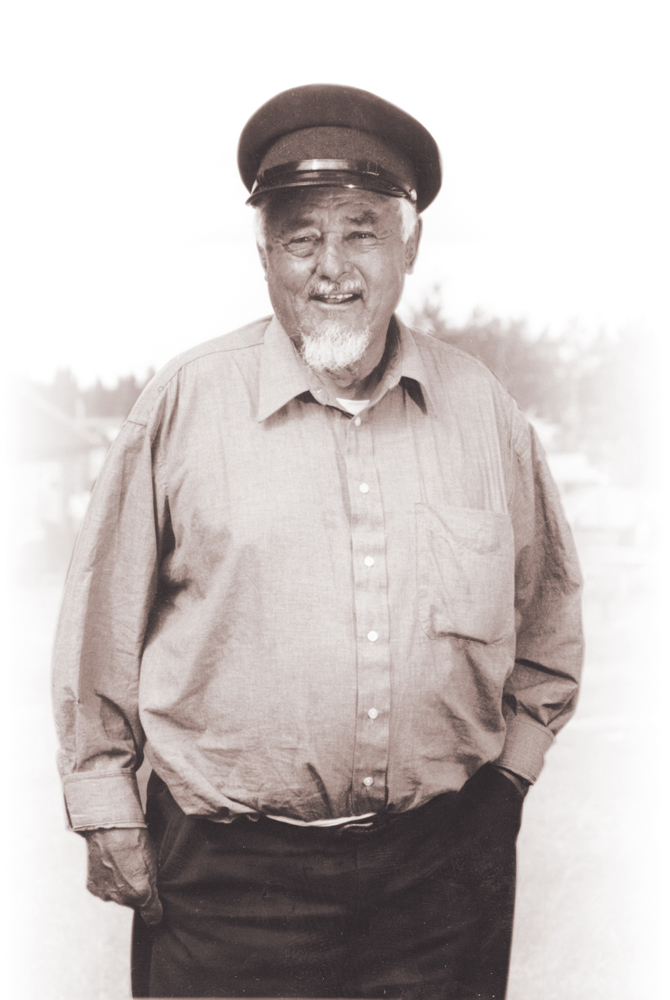

An amazing old man, Sam Blacksmith, the central figure in the National Film Board film, Cree Hunters of Mistassini, died May 14, at the age of, at least, 97.

He is one of the last remaining Cree hunters with a full knowledge of the bush life, men and women who had accumulated a vast storehouse of knowledge of the behaviour and biology of the animals around which they built their life, and whose attachment to the land, so rare among people nowadays, was an essential and irreplaceable value for all Canadians.

Through the medium of that film, which was produced in 1972-74 and achieved a large international audience,

Sam, with his simple but profound wisdom, became known and respected in many parts of the world as a quintessential spokesman for the central values of Cree life.

His answers to complex questions were deceivingly straightforward. We made the film at a time when the Crees’ ownership of their traditional lands was called into question by the James Bay hydro-electric project. Yet when we asked the question, “Do you own the land?” he didn’t embark on a politically-charged statement of ownership, but instead replied, “Well, people tell us we own it. But in reality, everyone dies, so no one can predict anything.” No anthropologist on earth would have thought of such an answer.

When we asked Sam, ‘Which season do you prefer?” his answer was equally simple, and equally expressive of the most profound Cree attitudes: “All seasons are good.”

When Tony lanzelo and I were appointed to make a film about Aboriginal rights in Canada, we went to Mistassini, where we had been before, to seek the co-operation of the community, and of individual hunters, in the making of such a film. We were both neophytes in the values and beliefs of the Crees, when we began to seek their co-operation.

It may have been because of the looming threat to their lands that Sam and his friends Ronnie Jolly and Abraham Voyageur agreed to allow us to accompany them to Sam’s land, several hundred miles north of Mistassini, between the Eastmain and Opinaca rivers. The territory was large, some 2500 square miles, and we were astonished when we saw that land, pock-marked as it was (and is) with a huge number of lakes and connecting streams. On one detailed map I counted some 800 lakes (not that the Crees themselves would ever have made such a count, that wasn’t their way). But Sam and his friends knew their way around that territory as if it were the back of their hand.

We flew into their camp first for three weeks in the fall, just after they had arrived, and were living in tents. We discovered them building a large wooden lodge which was intended to accommodate not only the 16 people of their three families, but also the six members of our film crew. They showed expert construction skills in taking the needed logs from the forest, trimming them, and putting them together to make the lodge, insulating them with peat moss gathered from the forest by the women and children.

With that work under way, they next got busy taking a census of the animals in their territory. They traversed the entire territory by canoe, identifying all the beaver lodges, the bear hibernation dens and other signs of animal life. This work had such a scientific precision that we were astonished, and pretty soon we realized probably no one had ever had the opportunity, given to us, to film everything done by such a camp of hunters. So, as the saying goes, from early on, we began to shoot everything that moved.

Sam, his wife Nancy, their daughter Rosie and son Malick were patience itself as we laboriously explained the shots we wanted to take, and the actions they had to embark on if we were to film them. So were the Jolly and Voyageur families, equally co-operative and long-suffering with our necessarily slow and cumbersome way of working. In some ways we were almost a figure of fun to them, for they were so used to zipping around in their canoes, and later in the year, on their snowshoes, that we were never able to match their expertise, and were never able to transcend the role – given to city slickers traditionally by Cree hunters – of bumbling white men in the bush.

Of course, we were utterly dependent on them for our survival. We had timed our fall visit to give ourselves a window of two weeks before the earliest known freeze-up so as to ensure we could get out of there. But the gods played a trick on us – the lake froze up while we slept one night, and in the morning Sam came into our tent and, knocking the frost off our roof and laughing uproariously, announced the lake was frozen over.

As a matter of fact, it was no laughing matter: we had eaten all the food we had taken in with us, and if we were to be stranded there for six weeks, would be thrown as a burden on the capacity of the hunters to catch enough food to feed us. The entire eastern seaboard was locked in under a vast weather system that prevented planes from flying. But on the third morning after the freeze-up we heard the drone of an airplane engine that had flown at a height of only 500 feet all the way from Chibougamau. It crashed through the thin ice at one end of the lake. We had to leave much of our stuff behind to ensure the plane could take off.

We returned to shoot the winter activities in March, to find the camp had had rather a hard time of it, not having found any big game (moose or bear), which would have eased the burden on the hunters. But now we were utterly astonished at the wide variety of skills revealed by Sam, Ronnie and Abraham. With monumental patience they led us to beaver lodges, where we filmed them setting the traps. Sam was almost as delicate as an orchestra-conductor as he whisked the snow gently to one side, cut a hole in the ice, and softly lowered the trap into the hole, connected to two poles, of which the mere movement an inch or so one way or the other would provide the signal that the trap had been sprung, and the beaver caught.

When we took this footage back to the NFB headquarters in Montreal, everyone who saw it was utterly fascinated by the expertise of these men. In that sense, Sam, Ronnie and Abraham provided a powerful demonstration to the outside world of the viability of Cree hunting life and its importance in the scheme of things, natural, human and animal. Twenty years later, in an account made of the work done by the NFB at that time, a producer, Colin Low, said that that one film -of the Blacksmith, Jolly and Voyageur families at work in the bush – had created such an impact as to have brought about a profound change in government policy towards the so-called Indians under their charge.

In this sense, Sam Blacksmith could be said to have been among the forerunners of the powerfully-effective outreach undertaken by the Cree people to the citizens of Canada in the following 25 years.

I honour him for that: but I loved him also for his wonderful humour, always ready for a laugh; for his marvelous patience; for his keen insight into the nature of human beings and their connections to nature. He was a remarkable man, recognized as such within the Cree community, of course, and it is well that we, outsiders, also should recognize him for the profound enlightenment about the Crees and their hunting life, that he so generously brought to us.