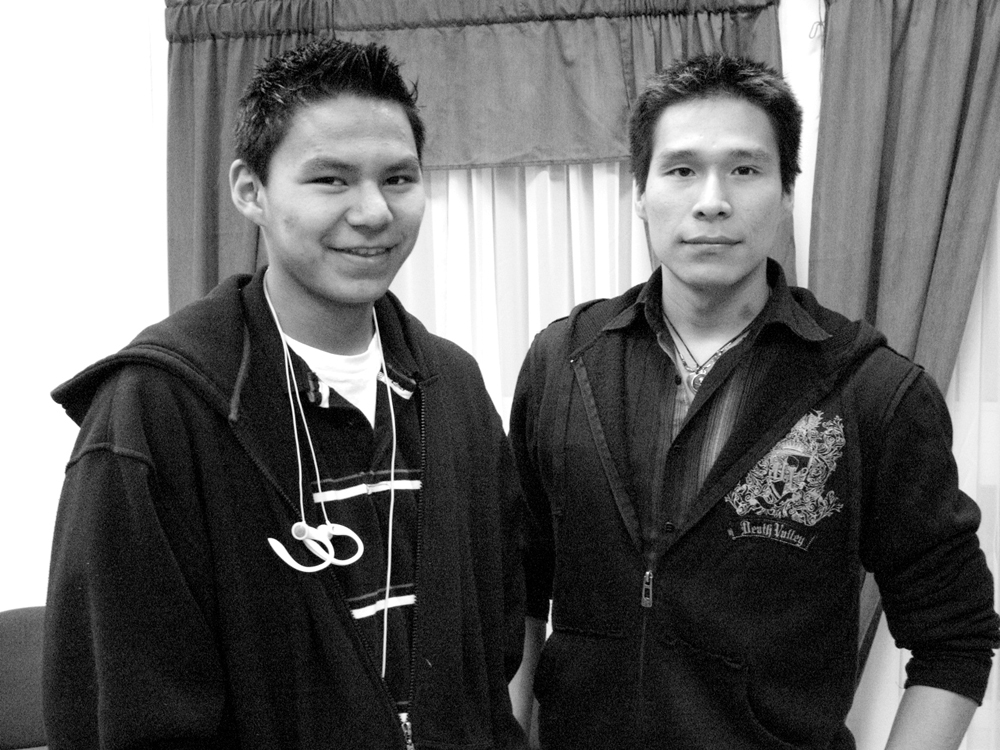

A lot can happen in five years. Just ask brothers Paul and Fred Rickard about their little festival that could.

“When the Weeneebeg Aboriginal Film and Video Festival started off five years ago, we thought it would be a one-time event,” Paul Rickard, the filmmaking portion of the dynamic brotherly duo told the Nation. “But we realized we really created something here and we continue to make strides through community support. That’s what it’s all about: we do it for the community.”

This year’s event ran March 7-11.

Rickard talked about the support from local entities and from the people in Moose Factory and Moosonee, and said that the filmmakers give back in kind.

“Weeneebeg is and always will be a festival where the community plays a major role in how we program our festival as well as how our filmmakers work with the community,” he said. “And there’s the youth component that our filmmakers facilitate, as well as showcasing works by youth.”

Rickard also added that before the festival became a reality, community members would always ask him what kind of films he had been making. They mentioned how hard they were to find on APTN. So part of the reason he and his brother started the festival was because of that. They got Cree Director Shirley Cheechoo on board, applied for a little bit of funding and the rest is history.

Rickard himself is a local legend, having been in the filmmaking business for 15 years, since his early 20s. He says that he has seven films to his credit, including the 26-part series Finding our Talk, which he counts as one. He has also worked on countless corporate videos and collaborative efforts over the years.

This year’s edition focused on women and their important role in the art of filmmaking. Moose Factory’s own Shirley Cheechoo showcased her latest work, the rough version of a three-part documentary-reality series called Extreme Beats.

The film takes a police officer from Manitoulin Island and puts her on a ride-a-long in Australia. It also takes a male Aborigine from Down Under to the foreign Canadian climate of Northern Ontario.

“It was an exchange of cultures,” said Cheechoo. “They taught each other about their culture and learned what it was like to be on the other’s beat.”

Weeneebeg also showcased talents like Gail Maurice (Memory in Bones), Elizabeth Day (Sunshine) and film legend Alanis Obomsawin (W’aban-Aki, People from where the sun rises).

“What really made it possible was the support from the community organizations and the people. So in turn, we make the festival about the community. One of the things we do is move the festival location every night from the Cree Ecolodge to the high school to the Elders’ centre,” said Rickard.

He also said that the programming is adapted depending on which venue the films are being shown in. For example a movie shown at the Elders’ centre would concentrate on things like language and hunting, whereas a screening for the youth would have content relating to them.

Ironically, Rickard did not have a film at this year’s festival. He joked about Cheechoo “going at a quicker pace than me,” since she has had films at Weeneebeg every year.

“As far as I remember growing up in Moose factory I’ve always been fascinated by that moving image,” he said. “My brother Fred used to run movies at the local community hall, like Jaws, Chinatown and The Exorcist. I remember watching them and being amazed.”

His brother Fred, who is the co-Executive Director and the Special Events Coordinator, said that the festival is becoming so big that he will be quitting his job facilitating transport at the local hospital to work full time for Weeneebeg in September.

“I never thought the length of how long it would last,” said Fred, who has volunteered his time up until this point. “We just took it year-by-year. Each year the community looks forward to this festival. And afterwards they let us know what they enjoyed, and what they didn’t. I’m looking forward to 2008, not the next few years.”

There are other activities throughout the year. For example, the Moose Cree First Nation Youth Services asked them to put on a workshop that teaches kids how to get comfortable doing public service announcements for a stop-smoking project. Seven kids worked on the project and their final results were screened at the festival.

This year, a special screening was held that showcased the sadness and despair of the residential school experiences of six Elders.

Called Muffins for Granny, the feature-length documentary by Nadia McLaren is very powerful. The film highlights six elders telling their stories about residential schools and how they’ve managed to overcome their problems through the healing process.

Rickard held a special screening of Muffins for Granny March 9 that attracted about 60 people. “We held it as a special screening because of the ongoing problem of residential school issues here,” he said. “It was a chance to create awareness for community members.”

The residential-school era, in which many children suffered physical, emotional and sexual abuse at the hands of their teachers and others at the school, is sometimes pushed under the rug. Rickard saw the need to get people talking and help them heal their scars.

He worked with Fort Albany, Kashechewan and Attawapiskat and some of their members came down for the special screening. He also worked with the James Bay Mental Health Program to provide counselors at the screening.

“We wanted to provide a support program for any viewers that might have problems with seeing the film,” he explained. “It shows how they came to be in the residential school system and what they had to deal with. The second half deals with the healing process and overcoming the abuse.”

The film elicited strong reactions, including a couple who walked out. “I talked to them after and they said that they went through residential school,” he said. “They couldn’t stay for the whole film.”

Cheechoo is proud Weeneebeg promotes women in the film industry.

“It’s always very important to showcase female talent because we’re always put on the back burner, especially native women filmmakers,” she said. “We always have more of a struggle getting funding or having someone take a risk on us as they would with male filmmakers. I’m sure in the white community women filmmakers have a hard time too, but if they were to choose between a white woman filmmaker and a native one, they’d go with the white woman.”

She was also pleased with the turnout and the rising local talent that can be credited to the festival.

“To me as a filmmaker it’s very important to go back because it grounds me,” said Cheechoo. “That’s where my parents are buried. All my relatives are there. But I think the most important thing is to hear the language. Where I live nobody speaks Cree. The language grounds me and helps me with my creativity. I think in my language and I write in my language, so it’s more creative to me.”

She says that when she uses English it comes from her head. “I feel when I use Cree it comes from my heart.”

Paul Rickard expressed gratitude to Air Creebec, Moose Cree First Nation, the Moose Cree Education Authority and the Ontario and Canada Councils for the Arts. He said that Weeneebeg will continue to prosper because of their help. He hopes the festival will one day help launch the career of a local filmmaker.

He also credits Indigenous Culture and Media Innovations out of Six Nations, Ontario and the Imaginative Film Festival in Toronto with lending a huge helping hand this year. Imaginative provided the youth component of films that were screened at the school while ICMI donated equipment for use in the workshops.

“When I was growing up there were never any outlets to learn about the arts or media arts,” he said. “To promote media arts within the community, we not only look at how we can get support for our festival, but how we can, as filmmakers and as a festival, support our community organizations. It works both ways.

“By having our festival we try to promote media arts as a form of a viable career for people. As artists we contribute to our community by the stories that we tell. We tell stories about our communities, the people within our communities and what happens in our communities.”