Two of the three chiefs most identified as environmental activists in elected Cree politics have been recently forced from office, one by an election loss and the other by term limits.

Abraham Rupert served Chisasibi for six years. He led his people through the Paix des Braves referendum, in which his community was the only one of the nine to vote against the agreement, through to the most recent referendum in November 2006 that saw his people turn thumbs down to the Rupert River diversion.

The other third of the trio, known for their publicity campaigns to save the Rupert, is ex-Waskaganish Chief Robert Weistche. He was forced out by his community’s two-term limit for chief.

Nemaska’s Josie Jimiken is the remaining “green” chief.

Rupert leaves a legacy of standing up for his community and always being there to listen to their concerns.

“During my two terms as chief I look back and I think I can honestly say I have no regrets,” Rupert said. “I spoke for and stood for what I believe in, what I said came from what my people told me. I had the honour of serving two terms as chief.”

Roderick Pachanos beat him in the August election by 90 votes. Rupert accepts the results and said that the people have spoken.

“It doesn’t matter how many candidates you have running for chief, you all have one goal in mind and that is to help the people,” he said. “I had my time.”

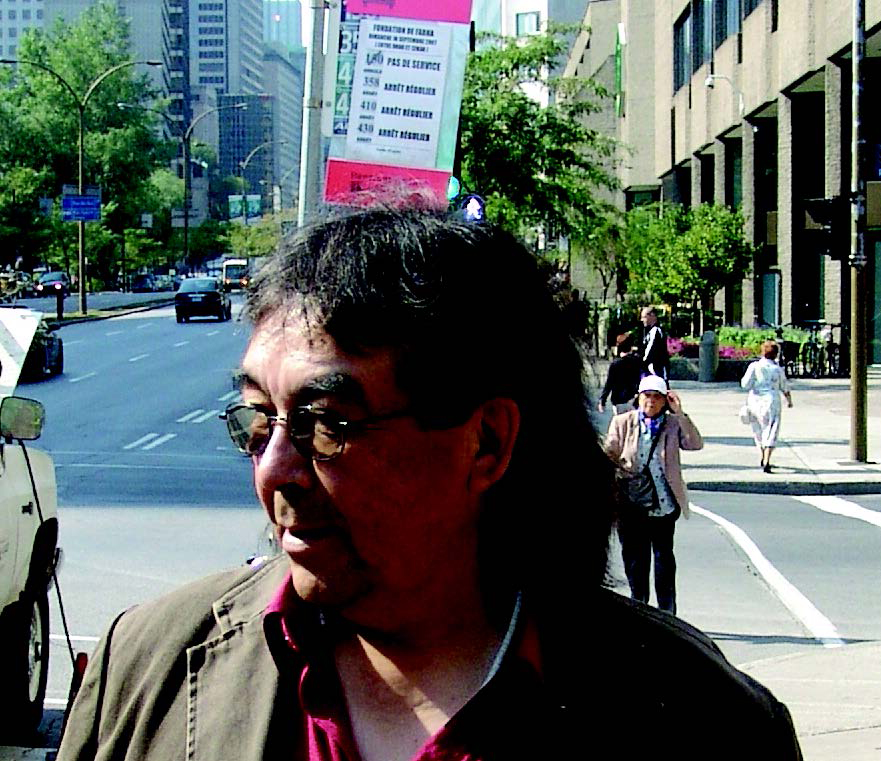

Rupert continued his fight for the Rupert River September 14 at a demonstration in front of Hydro Quebec’s Montreal office organized by non-native environmental groups Les Foundations Rivieres and Rupert Reverence. He said the fight is far from over and his new position out of office will help him voice more of his opinions.

“Some impacts from La Grande took a long time to show,” he said. “I think we’re at the stage where the community of Chisasibi understands fully what the impacts of the project are and how it affects the community physically and spiritually.”

Rupert said that the effects of the new project would not be seen for many years, which would be too late to reverse severe impacts on the land and wildlife.

“In the 1975 agreement there is a guaranteed level of harvest,” he continued. “Which means when I go hunting the harvest level of 30 years ago should be the same thing today. That is not the case. Along the coast, the eelgrass that the migratory birds fed on used to be abundant 30 years ago. But now that plant just doesn’t grow. That has not been addressed and I think it needs to be. It affects our traditional way of life.”

He also talked about the ice conditions being affected because of the diversion. He lamented that lives could be lost as people travel on the river by skidoo and run into danger spots.

“The rivers are the lifelines of the people,” said Rupert. “Many different things have changed because of the 1975 agreement. People no longer use the river as they did just 35 years ago. When you reduce a river’s flow by 70 to 80 per cent, there are going to be changes. They might not show up right away, but as we have seen through experience, it’s inevitable.”

Rupert said that instead of damming another river, there are viable alternatives like wind power.

“Chisasibi has been collecting data for a little over three years now. The numbers are showing that it is economically viable to produce energy from windmills,” said Rupert, of the Hydro-Quebec-approved project that would see up to 200 megawatts of electricity produced annually.

Rupert has confidence in Josie Jimiken, knowing full well that if push comes to shove, he is ready to fight for what he believes in.

“I believe that Josie is the kind of person who will fight this to the end,” he said. “There won’t be three voices, just one, but it can still be really strong. He believes what I believe that it’s too great a price and we will lose too much. I believe in him.”