This year marks the 40 anniversary of the signing of the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement (JBNQA). According to Grand Chief Matthew Coon Come the moment is an important milestone and a time for reflection.

“In celebrating the 40th anniversary of the JBNQA we have looked both backwards, to remind ourselves of just how far we have come and just how much we have accomplished, and also, we have looked forward to see future horizons, to set new challenges for ourselves to advance our nation-building agenda, and to address areas where we may need to take some corrective actions,” Coon Come told a gathering at Mistissini’s community centre to mark the anniversary on November 11.

“A lot of damage will be done in our land, such as the fish dying and water pollution. About 15 years ago, I remember the time when my brother and his family died of starvation and the same thing will happen again.” – CHIEF MATTHEW SHANUSH, EASTMAIN

Then-Premier Robert Bourassa announced the construction of the La Grande Hydroelectric Complex on April 30, 1971 – without notifying the Cree who lived in the territory. At that time, there was no Grand Council of the Cree. In fact there had never even been a meeting of all the Cree chiefs on Northern Quebec.

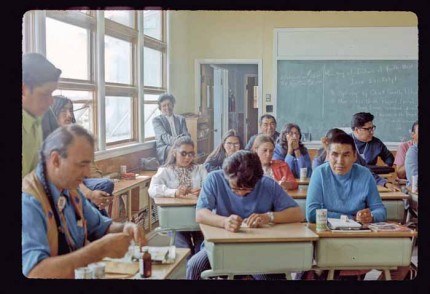

It wasn’t until June 29, 1971, that 28 Cree (councillors, chiefs and youth) from seven communities arrived and met in Mistissini to discuss what to do. At that time electricity, road access and even running water were relatively new. Most Cree communities didn’t even have these basic services.

The concerns were many: rising water levels that would flood hundreds of square kilometres of productive land; dead zones created by drastically changing water levels in response to electricity demands from southern communities in Canada and the United States; mudflats that would hinder animals’ access to water; water pollution and skyrocketing mercury contamination levels.

The Cree were determined to fight the project and were assisted by numerous people such as Harvey Feit, Ignatius La Rusic and James O’Reilly, among others. The Grand Council of the Cree first met at the Pal’s Hotel in Val-d’Or. On October 16, 1974, Chief Billy Diamond was elected the Grand Chief by a vote of 9-7, Chief Robert Kanatewat was elected as Deputy Grand Chief (10-6) and Abel Kitchen became the Executive Chief with a vote of 11-5. Violet Pachano was the recording Secretary at the time.

Crucial to the Cree position was the lawsuit heard by Quebec Superior Court Judge Albert Malouf. After seven months of testimony he granted an injunction to halt construction in 1974. A week later the decision was overturned on appeal. However, the Malouf judgement confirmed Quebec’s legal obligation to negotiate a treaty covering the territory, even as construction proceeded.

“We have already been asked not to eat fish, beaver and other foods from the water. We can’t catch fish now, and greater part of the hunting grounds will be flooded. The cemetery north of the village will be underwater. No human wants their mom or dad or child to be underwater when they were buried on dry land. Some of the people have been sent to Montreal because of polluted water, and sickness and also blood tests have been taken.” – CHIEF PETER GULL, WASWANIPI

“The water from the lake on our reserve is very salty and we get most our drinking water from the land, which isn’t salty. In winter, some saltwater comes from the Bay and cannot be drunk for a couple of days or so, therefore where are we supposed to get our drinking water? Fish, beaver and other wildlife would be also affected. There is already lots of salty water coming inland around the James Bay Coast.” – JOSIE SAM, FORT GEORGE

Negotiations began to create the JBNQA, the first modern treaty in Canada. While the desire of the Cree to keep the land pristine would die, the leaders were determined to get as much as they could for their people.

“The land remains, and will always remain, the central characteristic and the anchor of who we are as a people,” Coon Come told guests in Mistissini. “Everything in Eeyou-Eenou Istchee derives from that connection. Some people call that connection ‘fundamental’ – some call it ‘foundational’ and some call it ‘sacred’. Whatever we call it, it is that connection which defines us and which guides us as we imagine the kind of future we want for our future generations.”

Since the signing of the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement, Coon Come added, the Cree challenge has been to find a delicate balance between protection of the environment to preserve a traditional way of life and the development of natural resources for the use and benefit of Crees and their communities. “This is really what sustainable development is all about,” he said.

Since then, the changes have been many. “Even someone as young as I am,” Coon Come joked, “can remember using a yoke to get water, an axe to chop wood for the stove so we could make a meal, using an outhouse and being one of the lucky ones who had access to an outboard motor. A 25 horsepower was king in those days. Perishables like fish and other country food were shared freely as it would go bad without refrigeration.”

Even those who are not fulltime trappers still hunt, fish and gather the bounty of the land. In fact, concerns over the environmental, cultural and spiritual effects of the La Grande project led to the terms of the JBNQA. If the land could not be adequately protected from the La Grande project then how could we protect our way of life from the dominant culture? And in the end, how would we regain control over our future as a people?

“About 60 trappers at least trap around Rupert’s House. All wildlife, even rabbits, will be dead. We have food coming in to our reserve once a week and it is usually all gone in one day. In the meantime, while we are waiting for more food to come what are we going live on? Long ago, my hunting grounds had lots of beaver because sometimes about 10 men (with a quota of 60 beavers each) used to hunt in my grounds during the winter. They managed to survive on this even before welfare was ever issued to them.” – MALCOLM DIAMOND, RUPERT’S HOUSE

“We will also affected to a great extent but I would like to tell you that most of what we live from is half from the land and half from the Bay here. Most of the beaver trapped are around this area because Nitchequon has mostly otter and other types of fur. Our welfare program will likely go up because we can’t live off the land.” – CHIEF SMALLY PETAWABANO, MISTASSINI

“As a result of the struggles and the achievements which we have realized, we have established effective local and regional governments,” Coon Come observed. “It is through these governance institutions that we have made ourselves the decision-makers in striking that balance between the traditional way of life and involvement in a modern economy.”

It is this political advancement that made it possible to gain a great deal of control over economic development in Cree territory, he emphasized.

“If governance structures were not aligned with the rights of our people, if governance structures were not aligned with the demographic realities of our region, then there would have been a serious danger that the economic development within our traditional territory could be carried out without our consent and without benefit to our communities. But we made this connection fundamental to so many of our struggles so that now there can be no development of any kind within Eeyou-Eenou Istchee which has not met our standards of social acceptability.”

While the latest example of this is the denial of permits for Strateco to mine uranium, the best example is Hydro-Québec’s Great Whale Project. It was eventually shelved in 1994 due to the determination of the Cree people as a whole. That struggle demonstrated that the Cree were a political force to be reckoned with.

“We have been informed that there will be lots of employment during this project. If there is a dam near the reserve, take an example of Dawson Creek, B.C., there will be the white man to come in near the dam, set up a town and take over education, job opportunities and language. Indians will have no job, go to town and drink, will not be accepted by the white town, unwed mothers and just be treated like a dog by the whites.” – CHIEF BILLY DIAMOND, RUPERT’S HOUSE

However, even 40 years after the JBNQA agreement, Cree leaders in Quebec must still deal with myths about Aboriginal peoples.

“We in Eeyou-Eenou Istchee have dispelled the persistent myth in Canada that Indigenous peoples represent an obstacle to development,” Coon Come noted. “According to this myth whenever there is a possibility to develop resources and where there is a claim involving Indigenous traditional territories, our peoples will create legal and political impediments to such development projects. The myth implies that Indigenous peoples do not really wish to be participants in the mainstream economy.

“Unfortunately, the perpetuation of this myth has prevented natural resources and economic development within Indigenous territories from transitioning towards a model that includes our participation and that acknowledges our rights. For Canada as a whole, the perpetuation of this myth has resulted in sadly missed opportunities to resolve long-standing disputes between First Nations and the Crown.”

Coon Come added there is another myth that affects the Cree Nation. “That is the myth that we cannot make it as business people or as enterprises unless we have hand-outs, or unless we receive special treatment… We need to believe that we can carry our own weight in all areas of the life of the Cree Nation and we need to act on that belief, for no other reason than it is true.”