It is early morning on Fort George Island, and 87-year-old Jade Matthew is building a teepee with her husband. Grabbing two long birch poles tied together at one end with bright red rope, they place the bottoms in the soil, forming an inverted V.

Jane moves deliberately, methodically placing the rest of the poles until the structure is formed. Two of her sisters – also both in their 80s – sit under a pine tree, watching.

The couple then hoist a canvas tarp around the bottom two-thirds of the teepee. Tying ropes to another tarp, they manoeuvre it into place, covering most of the top third but leaving a three-foot hole for the smoke.

“Everything tastes better when cooked over a fire,” she tells me, taking a break from the work. “The tea, the food, it all tastes different.”

In a tight-knit Cree community of about 2,000 here, Jane, her husband and sisters all once lived in weather-beaten homes that lacked many modern comforts, such as running water. But in 1980 the community voted to leave.

The island, Hydro-Québec engineers told them, was unsafe. Just upriver, Hydro-Québec was building La Grande 2, a $3.7 billion project that remains Canada’s largest hydroelectric power station. And once completed, it would permanently alter the flow of La Grande River, which they said would cause erosion on the island.

A bigger worry was if the dam failed and a wall of water would submerge the island and its people.

About 200 homes were removed, cut off at the bottom, placed on barges and relocated to the new mainland community of Chisasibi. The single-family homes were neatly placed along a suburban grid that one can see on the outskirts of any Canadian city.

Fort George, however, has remained an important place for the people of Chisasibi. Each summer, Jane and much of Chisasibi return for the annual Mamoweedow festival. It’s a week full of laughter, traditional food and reaffirming connections – both to traditional Cree culture and other community members.

Like many First Nations communities, Chisasibi is growing: the 2006 census lists 4,200 residents, though that number is likely higher now. And it boasts a young population, with 35% of its population under the age of 14.

As down south, many complain that the increase in technology – the cellphones, computers and televisions – are causing the community to splinter, losing some of the closeness that marked life on Fort George Island.

Not so different

Jane’s daughter, Emilie Matthew, helped go door-to-door to gather ballots on whether or not the community should move to Chisasibi. It was contentious, she says, declining to elaborate any further.

Emilie and her husband, Ernie Sam, grew up on the island. They both attended residential schools, she at an Anglican school, he at the Catholic. School was strict, staffed by cold teachers with heavy hands. Being separated from their parents was challenging.

Summers, however, were different. It was theirs. Their parents returned to the island from their bush camps, and the kids were free.

Emilie would follow her mother and sisters through the island’s forests, collecting berries and leaves to make Labrador tea. She learned how to hunt, build a teepee, and cook traditional foods. “I wanted to learn. So I always asked questions,” she explains.

Ernie now runs a construction company out of Chisasibi and remembers his youthful summers with deep affection. There was a sawmill on the northern tip of the island that he said would dump sawdust in giant piles on the beach. He and his friends would run to the top and then jump down, landing halfway down the slope.

The picture they drew – of an island that represented freedom and fun – paralleled the atmosphere of Mamoweedow. In the afternoon, teenagers threw footballs and Frisbees at a large grassy area while kids played with skipping ropes. Older people and parents hung out on picnic tables, talking among themselves, reconnecting.

A young girl showed her friends a baby bird she had found. One of its wings broken, the bird sat quietly in the girl’s pocket.

Other kids just chased each other around, playing late into the evening. There’s no curfew for kids during the festival, one parent told me, nor is any alcohol is permitted on the island. Some credited that rule with helping to create a safe space, where they feel comfortable giving kids more freedom to roam about.

The Big Tent

Every night, people gathered in the big tent, a 100-foot long hall lit with long lines of florescent bulbs hanging from the ceiling.

Some took part in square dances with others played games. Karaoke and an open mic catered to those who wanted to perform.

Adele Snowboy-Napash was there throughout, late into the night. For the past six years, she has served as the president of the event’s organizing committee. Along with her sister, Anne-Marie, she runs most of the games and introduces the musical acts.

“Did you hear my Cree,” she said with her quick, infectious laugh during a rare break. “Even I was making some mistakes. They were laughing at me!”

One of the goals of the festival is to strengthen the Cree language and keep it relevant to young people, she said. Some of the familiar music performed was translated into Cree. A group of women sang versions of “Jolene” and “Coal Miner’s Daughter”.

Adele said it’s important for people to be immersed in traditional culture, and to realize that they can survive and thrive without modern technology. That said, going back to basics could be challenging for some. Even her grandson, who spent the opening day at the festival, couldn’t handle it. After one night he wanted to go home to his video games, television and Facebook.

“We’re going to bring him back,” said Adele. “I feel bad that he’s missing this.”

Cooking for many

The festival is funded with a grant from Niskamoon, fundraising, and sometimes money from the band council.

Some of the budget money pays for food. Two meals – breakfast and dinner – are provided to everyone that attends, all prepared and offered in a massive, 20-foot tall teepee. It’s a welcoming space, with a constant stream of kids and adults filling up on juice, coffee and fresh bannock throughout the day.

An eight-foot cooking fire pit occupied the middle of the teepee. A giant vat sat on a grill atop it, boiling bear meat. Bannock was wrapped along the end of five-foot sticks and propped up on the edge of the fire pit. Moose meat and blowfish were smoked high above the fire.

Country music played in the background from a radio in the cooking section. Several chatting, laughing women were cutting carrots, washing dishes and frying fish.

One of the first-time cooks was Roselea Bearskin. At 21, she’s been coming to Mamoweedow her entire life. For Roselea, Mamoweedow is a way to “get away from everything.” Life in the Chisasibi can be challenging, she noted. Mamoweedow is like a vacation, a week to connect with family and community over good food and games.

During this week she was pulling double duty. In addition to the cooking, she took care of her two younger sisters, who ran around at night with bright LED lights strapped to their heads.

Her favourite festival memories were from the same age, when she took part in the games in the big tent. She hasn’t done that for a while, since she was 15. “I started growing up – maybe a bit too fast. And right now, I’m too shy to play in front of a lot of people.”

Roselea has done a lot of traditional cooking at home with her family, and she moved with confidence, rotating the bannock and ensuring it’s properly cooked. But this was the first time cooking on a major scale. She said she learned new things from her Elders every day.

Back with Jane

Not everyone ate dinner in the big teepee. For Jane and her family, preparing food was a big part of their fun.

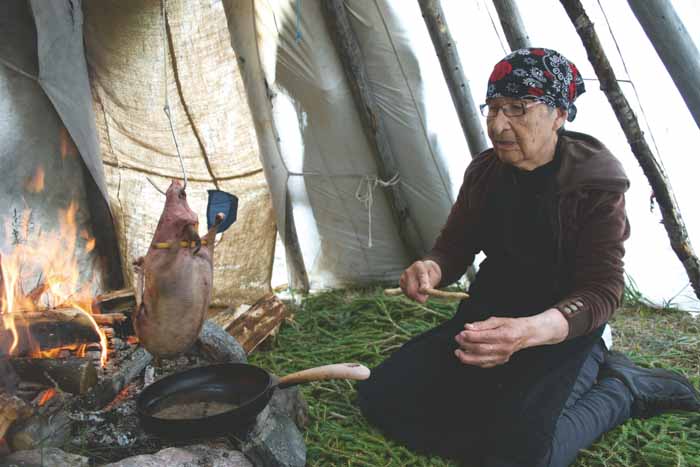

One rainy morning she was roasting a duck over the fire. It hung beside the fire, from a rope with four knots evenly spaced apart. Using a stick to wind it, the duck slowly turned beside the small fire as the cord unwound. “You know it’s ready when it begins to steam from the sides,” she explained.

Her daughter, son-in-law, sister and great-grandson sat opposite as she relaxed, lying on her side on the soft, green pine needles cushioning the floor of the teepee. They talked among themselves in Cree, but there were long periods of silence, when all you hear is the sound of the heavy rain beating against the canvas. She likes that sound, Jane murmured as the tantalizing aromas of duck and bannock filled the teepee.

There’s something tremendously satisfying and tranquil about the whole experience, just watching food cook on an open fire, with three generations of a family. It’s a scene repeated in dozens of families around the island. They come together, hang out, and get to know each other on a deeper level, free from the many distractions of modern life.

The spirit of life at Fort George lives on at Mamoweedow, revisiting a time when summers were free and life was much more simple.