Montreal’s Cabot Square stands at the corner of St. Catherine and Atwater streets, a gateway between the noise and chaos of the grimy downtown to the east, and the wealthy tree-lined streets of Westmount in the west. For decades, the park has been full of homeless people, many of them Inuit or First Nations. But after a long facelift, the park now boasts something entirely new: the Roundhouse Café, an Aboriginal snack bar that stands to bring the Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities together at that literal crossroads.

Montreal’s Cabot Square stands at the corner of St. Catherine and Atwater streets, a gateway between the noise and chaos of the grimy downtown to the east, and the wealthy tree-lined streets of Westmount in the west. For decades, the park has been full of homeless people, many of them Inuit or First Nations. But after a long facelift, the park now boasts something entirely new: the Roundhouse Café, an Aboriginal snack bar that stands to bring the Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities together at that literal crossroads.

“At one time this place was dangerous,” manager Al Harrington recalled in an interview with the Nation. Harrington is Ojibway from Shoal Lake, but has lived in Kanesatake for nine years, during which time he worked as an outreach worker for the Friendship Centre. “Even when I was on street patrol, we used to come around this area. It was pretty dark with the trees, coming in here.”

Over the last year, the Cabot Square project has completely redesigned the park, which was often full of people reclining under trees drinking wine or large bottles of cheap, high-alcohol beer. For homeless advocates, the park was certainly imperfect, but at least it was a place for homeless people to congregate and meet one another. Some feared the redevelopment would force them out, leaving one less place where homeless people could go.

“That was one of the biggest initiatives in the Cabot Square project; they wanted not to kick the people out, because they’re just going to move on to somewhere else,” Harrington explained. “I know at one time the problem was they wanted to kick them out, and they started migrating toward Westmount. Westmounters started seeing Inuit in the park, and they started making complaints.”

Harrington and fellow Friendship Centre outreach worker Joey Saganash sat down with Westmount officials to try to explain the situation and its ramifications. Those discussions occurred at the beginning of a long chain of events, the end of which is the current Roundhouse, which employs Indigenous people who have been on the street themselves. As the program was being developed by the Cabot Sqaure Project in partnership with L’Itinéraire (a magazine sold by homeless people and those who have been on the street), planners asked Harrington to manage the café because he had experience running a restaurant in Kanesatake.

“I thought the people they selected were good,” Harrington said, noting that the café needs to serve both the homeless in the park and those venturing into the newly tidied square from the rich neighbourhood to the west. Behind him, worker Shirley DeWind worked constantly, serving customers, making coffee and tidying counters.

“Shirley and Brandon [Perreault], they’ve been there and done that,” Harrington said. “They’ve been in that situation and they’re here to change their lives around and get that second chance, getting experience on the job in customer service and setting an example for the ones out there.”

Setting an example is part of the idea, Harrington said. The Roundhouse presents non-Indigenous locals with homes the opportunity to interact with and build friendships with Indigenous people who have been on the street.

“Our customers and the residents love the place, because they feel a sense of coming together,” he said. “They feel safer and they love the park. They’re also getting educated by our staff and by the outreach workers in the back that homelessness will always be a problem, and it’s never going to go away. But if we can make another person’s life a little bit better, we should try.”

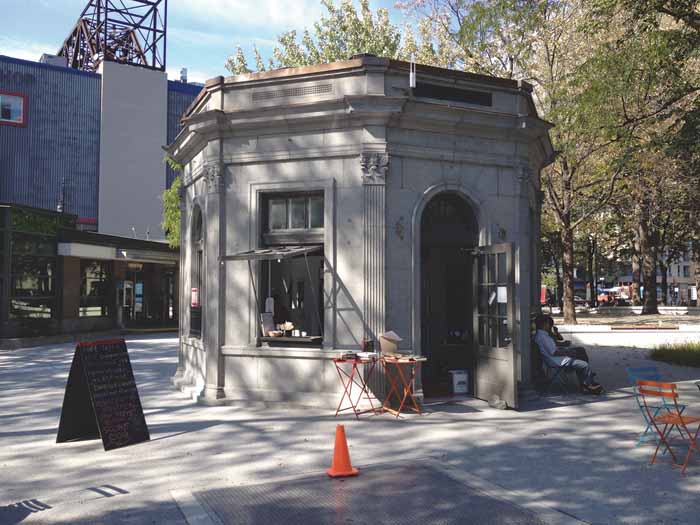

In Ojibway culture, Harrington explained, a Roundhouse plays a role similar to the Longhouse – it is a gathering place in which all are welcome, where the community can meet, eat and talk together. The Roundhouse café is occupied in a small almost-round building and serves classic Native fare like bannock and strawberry drink alongside coffee, soup, chili and the only scone-dogs in Montreal. It boasts a book exchange, and encourages readers to take or leave a book, either for the afternoon or forever.

But most notable among the café’s developments is the “Pay it Forward” board, allowing diners to pay extra to put up a free cup of coffee or plate of bannock or chili for someone who can’t afford it to enjoy later on.

“When clients see us do that, and they see that connection, it warms their hearts too,” Harrington said. “That’s what really makes this place special. We’re all people. We all still need to have that caring sense. We’re building bridges here. We’re getting people coming up every day, many of them not even buying something for themselves, but just putting something on the Pay it Forward.”

Harrington’s contract is only a year long, and he doesn’t know whether it will be renewed once the café is up and running.

“A lot of people are saying, ‘It won’t be the same if you leave,’” he explained. “I say, ‘It will be. You guys started it.’ It’s a community place where staff is going to come and go, but the heart of the building is the way you guys made it, and it’ll always be like that. If I’m not here, I’ll come and visit and support it. But the Pay it Forward, the community created that together. The staff will always be smiling and happy and willing to go the extra mile.”