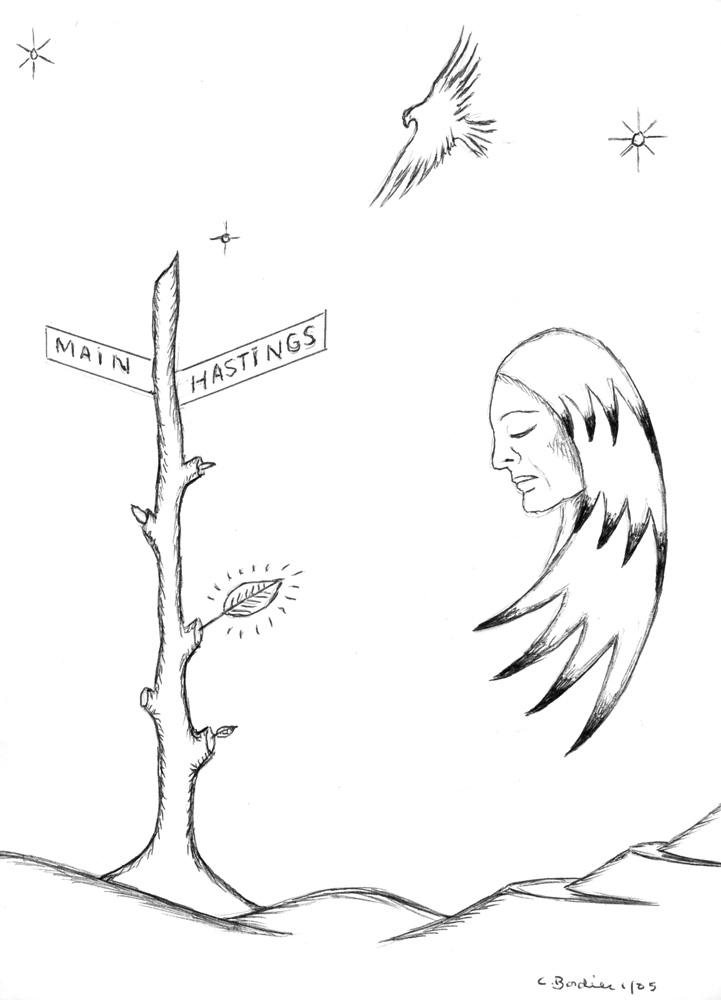

For many people across Canada Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside conjures up images of hopelessness, shattered dreams and drugs and prostitution. Part of the reason Aboriginal women turn to this kind of life is because they’re Native. Christiane Bordier explains why.

Vancouver! The name conjures up beautiful visions of the mountains, the ocean, sunsets at English Bay or Jericho Beach. The city is known all over the world for its beauty and calm.

But the flip side has been carefully hidden by the tourist trade, governments and local residents. Wedged between Chinatown and Gastown, the Downtown Eastside is 10 blocks of skid row, abandoned buildings, drugs, alcohol, prostitution, and homelessness that have for about 30 years been the cancer of Vancouver.

It has been called Canada’s Calcutta, the poorest postal code, the biggest urban reserve and the biggest open drug store of Canada. Every city has a “dumping ground,” but nothing compares with the Downtown Eastside.

There are many reasons for this fiasco: the breakdown of social programs, the emptying of psychiatric hospitals, the reduction of welfare rates, the cutting down of social housing, the growing poverty on the reserves, with many residential school survivors. It is estimated that 70 per cent of the neighbourhood population is First Nation.

The survivors and their children are still suffering the consequences of the residential schools.

Personally, having been born in Montreal in 1944, I was in the Chappelle de la Reparation orphanage for two-and-a-half years. There, someone scorched my left cornea. I received no treatment and lost the vision in my left eye. I grew up when the Church had absolute power, controlling all aspects of life in the province. It marked me forever.

Alcohol is a big problem also. For 18 years Chinatown openly sold 39 per cent alcohol rice wine for about $3 a bottle, killing many people every year. Finally the government was able to put it in liquor stores, but it is legally back on the shelves at 9.9 per cent.

For many years women went missing. Friends and families reported their disappearance to the Vancouver Police Department. The police were indifferent, implying they ran away, moved, or left without an address.

Many of the missing sex workers were Native.

The number of missing kept growing, the police did nothing and society didn’t care about “junkie hookers.” The families and friends worked hard to get the media, police and government to acknowledge publicly that something very wrong was happening.

In 1999 the first poster of the missing women was published, offering a big reward for information. Still more women kept disappearing. But now it was public and strong pressures were put. Then, a Missing Women Task Force was set up.

The situation was very complicated because the people had a deep mistrust of the authorities. For a long time there were rumours of strange goings-on at a Port Coquitlam farm. They were ignored.

Then, on February 1, 2002, a warrant was issued to search that farm. Personal belongings of many missing women were found as well as the remains of Serena Abotsway and Mona Wilson. It led to the biggest mass murder investigation in Canadian history.

So far, the remains and DNA of 32 women have been identified, including three “Jane Does.” Robert Pickton has been charged with the murder of 15 women, and is awaiting trial.

I personally knew Serena quite well. She was addicted to heroin, in the sex trade, and homeless on and off since she was 14.

I had many conversations with her. Under her tough exterior, I found a tough and warm woman. One day, late May, 2001, she got into a screaming match with someone. I took her aside, gave her a smoke, calmed her down, and told her to be careful: “I don’t want to hear they found your body somewhere.” It was the last time I spoke to her. I saw her from time to time and said hello.

Early August, I saw her walking on Powell St. with a scruffy, dirty man. It felt strange to me. I tried to talk to her but she ignored me. He was filthy, his clothes were ripped, he looked around 60, but, unfortunately, I didn’t think much of it at the time. In retrospect, for a long time I felt terrible guilt. Seven months later, when the case opened at the pig farm, I saw the picture of Pickton, it was him! As far as I know, I was the last person to see her alive.

I contacted the police, and was interviewed by two RCMP officers. They were very kind and sensitive.

In 1996, Pickton was charged with the brutal stabbing of his then girlfriend, but the charges were dropped because “the witness was not reliable.” The mentality was, “Who would believe the testimony of a junkie hooker.”

Pickton allegedly did not act alone. Many people were involved. He was the recruiter, coming regularly to the Downtown Eastside to pick up women.

Late March 2002, the Coquitlam reserve set up women ceremonies for a few days. I went with other women and some of us went to the entrance of the farm to pay our respects. A few weeks before, I made my first ceremonial drum at Carnegie Centre. I used it there for the first time. We smudged, played drum, and cried. I remembered the last thing I said to Serena, and here I was where her body was found. I almost went to pieces with grief and guilt.

Later, I spoke to many people and I know now, even if I spoke to her, that day I saw her with Pickton, it would have made no difference.

Violence against women is enormous. Almost every week, a woman dies violently. Recently, at Crab Beach, a woman was running bleeding and screaming, a police car found her, a man was stopped and they found videos of many local sex-workers allegedly being beaten and tortured.

But the Downtown Eastside is not all dark and evil. Under all those visible tragedies, there is a strong undercurrent of great beauty of the Spirit. We are a powerful community of many artists, writers, volunteers, limited by the murderous welfare rules and the negative perception of us from the outside.

Every February 14, we have a Women Memorial March to remember the missing and murdered women. I am very involved with the march. It is growing every year.

On June 21, we celebrate Aboriginal Day with a big feast, drumming, and games at Oppenheimer Park.

The second week in August, at the same park, we have a Vision Quest, during which we fast and camp on the ground, praying for healing in the neighbourhood.

Poverty and pain brought us great spiritual strength. We have become warriors for social justice.

A song was given to women in a sweat lodge in the 1990s. “The Women Warrior Song” has become the anthem of the Downtown Eastside. We sing it at every gathering, march, feast, protest, memorial, and special occasion. I went to more funerals and memorials in the last five years than the first 55 years of my life.

Even if I came into money and had a financial choice, I would choose to stay here. For the first time in my life, I am home.

For the last few years, the situation is improving. The Needle Exchange Program has reduced the HIV and Hepatitis C rates. The new onsite safe injection site has already reduced the overdose deaths. In the mid-1990s an average of 300-plus overdose deaths occurred yearly. Soon, a harm-reduction program will start by giving medical heroin to some addicts on a trial basis. The “war on drugs” is an abject failure; other approaches have to be tried. Now, we see some hope at the end of this dark tunnel.

All my relations,

Chistiane Bordier.